voltages, step-down voltages, or both.

Disregarding the inherent

losses in transformer action, the following rules apply:

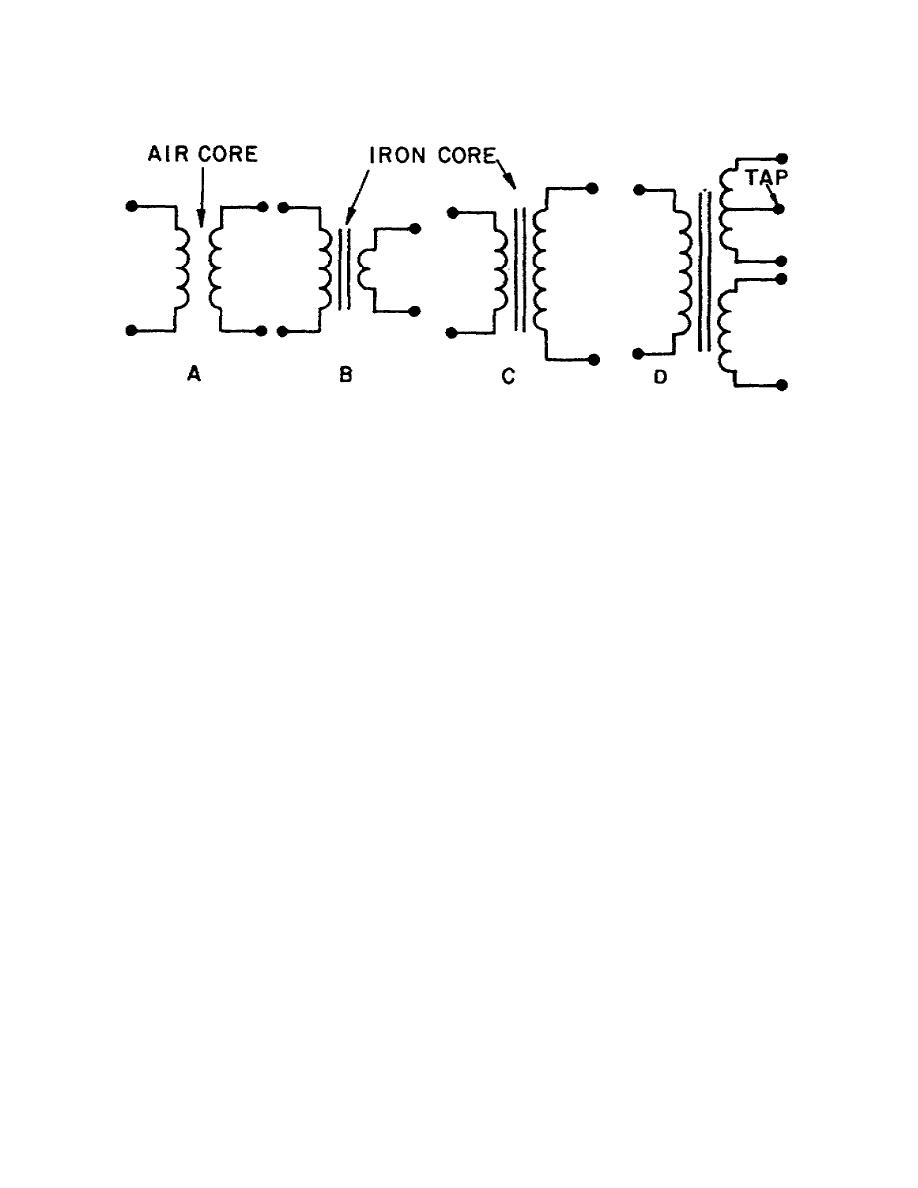

Figure 1-13.

Transformers.

(1) If the number of windings in the primary and secondary is

the same, the voltage and the current in the secondary will be the

same as in the primary.

Figure 1-13A illustrates a 1:1 ratio

transformer.

(2) If the number of windings in the primary is greater than in

the secondary, the voltage will be less in the secondary and the

current will be greater. For example, if the number of windings in

the primary is twice that of the secondary, the voltage in the

secondary would be half that of the primary, and the current would be

double that of the primary. Such a transformer is referred to as a

step-down transformer. Figure 1-13B shows the symbol for a step-down

transformer.

(3) If the number of windings in the primary is less than in

the secondary, the voltage in the secondary is greater than in the

primary, and the current will be less. For example, if the number of

windings in the secondary are three times that of the primary, the

voltage in the secondary will be three times that of the primary, and

the current will be one-third. Such a transformer is referred to as

a step-up transformer.

Figure 1-13C shows the symbol for a step-up

transformer.

Transformers have many configurations to meet the needs of the

circuits they supply. Just as with inductors, transformers may have

an air core, a fixed iron core, or an adjustable iron core.

The

output may be varied by adjusting the primary, the secondary, or the

core. The secondary may be tapped to provide a variety of outputs in

the secondary, or the transformer may have more than one secondary to

provide separate outputs (see

9

OD1725

Previous Page

Previous Page